In a much-quoted exchange, a pollster once asked an Australian voter the following question: “Going into this election, and thinking about the average voter, what would you say is the biggest problem facing Australia today – ignorance or apathy?”

In a much-quoted exchange, a pollster once asked an Australian voter the following question: “Going into this election, and thinking about the average voter, what would you say is the biggest problem facing Australia today – ignorance or apathy?”

The voter replied, “I don’t know, and I don’t care”.

As we approach the South Australian State election, our key messages are crystal clear:

1. Competence & Care

Are you competent? And do you care?

Whether it’s your doctor, your mechanic or your child’s teacher, all you want to know about them is: ‘Are they competent? And do they care?’

At the Australian Family Party, we stress the importance of appointing capable people.

2. Understanding the Times

In uncertain times, the choices we make shape our future.

At the Australian Family Party, we are focused on electing strong principled leaders — people who understand the times and know what needs to be done

3. Climate Change

If we wish to have a strong enough economy that can build a strong military to be able to defend ourselves against looming regional threats, then we are going to need to abandon our obsession with useless forms of energy generation, such as wind, solar and green hydrogen.

There is no climate emergency, there is no cause for panic.

4. Israel

In today’s uncertain world, the choices we make as a State and as a nation will determine our future. At the Australian Family Party, our support of Israel is what sets us apart.

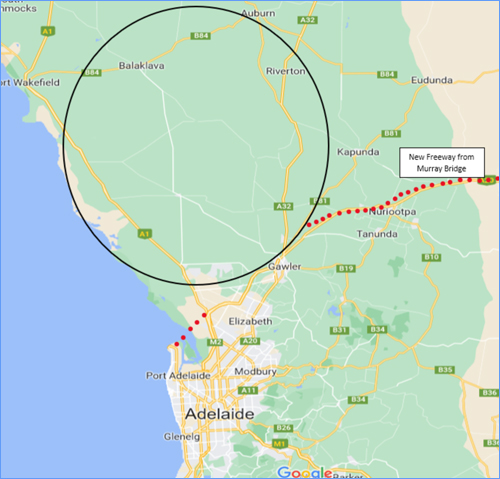

Protecting our nation, strengthening our economy, and supporting our families is the foundation of a strong society. Australia – South Australia in particular, given its climate and topography – would benefit enormously from a closer relationship with Israel.

5. Let’s Make South Australia Great Again

Many South Australians can probably remember the time when more than a dozen of Australia’s top 100 listed companies had their head offices in Adelaide – News Ltd, Fauldings, Southcorp, Elders, Normandy Mining, Adelaide Bank, Adelaide Brighton, Standard Chartered Finance to name just a few. Today there’s just one – Santos (and even Santos is on borrowed time).

At the time of Federation, South Australia led the constitutional debates and had an influential hand in shaping the new Commonwealth of Australia.

For decades after, Adelaide was Australia’s Number 3 city – bigger and more prosperous than either Brisbane or Perth.

South Australia prospered when it supported people who made things, grew things, and built things.

Over recent years, some bad ideas have found their way into the South Australian Parliament resulting in some awful legislation being passed. These include: the ‘Urban Growth Boundary’ which gave us severe housing affordability problems; ‘Transforming Health’ which led to chronic hospital ramping; ‘Renewable Energy’ which resulted in SA having the most expensive power bills in the nation; ‘Anti-Life’ legislation that has given us those grotesque abortion-up-to-birth, assisted suicide and prostitution laws.

In addition, a conga-line of rent-seekers, bootleggers and carpetbaggers looking to exploit the public purse. These crony-capitalists, who base their business models on schmoozing politicians and convincing them that their particular goods or services are essential – and that the government should either pay for them or limit competition to providing them – have essentially created another layer of taxation.

This is important as South Australians already pay enormous amounts of tax in the form of GST, stamp duties, registrations, and numerous other levies and taxes hidden in water and power costs.

When state governments privatised SA’s water and power utilities, for example, they did deals with the purchasers permitting them to increase power and water charges in exchange for a higher purchase price of the utility – just taxation by another name. Consumers simply ended up paying more for their power and water. On top of that, utilities such as SA Water, then pay ‘dividends’ to the SA state government every year – ever more taxation under a different guise. SA Water has paid over $3bn in ‘dividends’ to the SA State Government over the past ten years. That $3bn should have been used to provide much-needed water infrastructure.

Yet in spite of all the revenue and dividends collected from SA taxpayers over the past ten years – up from $12bn in 2015 to $17bn in 2025 – the State Government’s reliance on subsidies from the other States to meet its spending commitments has also risen from $7bn in 2015 to $12bn in 2025, taking the SA State Government’s total spend from $19bn in 2015 to $29bn in 2025!

Why the other States continue to put up with South Australia’s flagrant spending habits is beyond me.

Likes and Dislikes

As you would have gathered, at the Australian Family Party:

We like …

South Australia, Australia, Farming, Mining, Small Business, Free Markets, Free Speech, Property Rights, Home Ownership, School Choice, Income Splitting, Traditional Family Values, Pro-life, Low Immigration, Australia’s Defence Forces, Israel.

And we dislike …

Big Government, Big Business, Big Unions, Rent Seekers, Wind Turbines, Solar Farms, Green Hydrogen, Net Zero, The Voice, Toxic Algae, Ambulance Ramping, Urban Growth Boundaries, $50bn State Govt Debt, Digital ID, High Immigration, High Crime Rates, Transgender Ideology, The UN, The WEF and The WHO.

Standing Guard

Standing Guard

The key role of an independent or minor party member of parliament is that of a gatekeeper – ‘standing guard at the gate’ to prevent bad laws getting into the Parliament – someone who will ‘sound the alarm’ when dodgy legislation is presented to the parliament.

If Parliament House were a night club, they’d have a bouncer on the door only admitting those who would add value! Undesirables would be turned away.

As a former Senator, I know how to stand up to destructive policies and how to stop laws that drive up costs, disrupt society and make life harder for everyday Australians.

Walk …. Get Fit …. Go Letterboxing ….!

As we often say, it’s one thing to have an opinion – it’s a very different thing to support a cause.

With summer approaching, what better time to get fit, go for a walk …. and do some letterboxing!

Can you do some letterboxing in your area? As few or as many letterboxes as you like would be just fine.

Note: Political material is not junk mail. It is defined and protected by legislation as political communication.

If you would like to do some letterboxing, please let us know here (choosing ‘Admin’ as the recipient).

Thank you for your support.

In Act 1 of Shakespeare’s great play Macbeth, the three witches appear before Macbeth and his friend Banquo. The witches predict that Macbeth will be king, and that one of Banquo’s sons will also be king one day.

In Act 1 of Shakespeare’s great play Macbeth, the three witches appear before Macbeth and his friend Banquo. The witches predict that Macbeth will be king, and that one of Banquo’s sons will also be king one day. In our Newsletters this year we have covered everything from the Voice bomb to the atom bomb, from Israel to industrial relations, from Gough to the Gulags, from federalism to forgiveness, from taxation to Truman, and from housing to Hamlet – and a whole lot more in between.

In our Newsletters this year we have covered everything from the Voice bomb to the atom bomb, from Israel to industrial relations, from Gough to the Gulags, from federalism to forgiveness, from taxation to Truman, and from housing to Hamlet – and a whole lot more in between. It is two years since we launched our

It is two years since we launched our  Frederick Douglass (1817–1895) is considered by many to be America’s greatest African American. Along with Booker T. Washington and Martin Luther King, these make up their top three.

Frederick Douglass (1817–1895) is considered by many to be America’s greatest African American. Along with Booker T. Washington and Martin Luther King, these make up their top three. As the late Texas politician Robert Strauss used to say, “You can fool some of the people all of the time – and they’re the ones you need to concentrate on”.

As the late Texas politician Robert Strauss used to say, “You can fool some of the people all of the time – and they’re the ones you need to concentrate on”. In his fascinating book, A Theory of Justice, the American moral, legal and political philosopher John Rawls promotes an idea called the Veil of Ignorance.

In his fascinating book, A Theory of Justice, the American moral, legal and political philosopher John Rawls promotes an idea called the Veil of Ignorance.