The story is told of the UN Secretary-General proposing that, in the interests of global peace and harmony, all the world’s soccer players should come together and form one ‘United Nations Global Soccer Team.’

The story is told of the UN Secretary-General proposing that, in the interests of global peace and harmony, all the world’s soccer players should come together and form one ‘United Nations Global Soccer Team.’

“That’s a great idea!” said his deputy, “but who would we play against?”

“Israel, of course”, the Secretary-General replied.

There is no mention in the Bible of Adam and Eve ever doing anything to provoke or anger Satan.

Adam and Eve were just minding their own business and enjoying all the benefits that God had provided to this perfect couple.

So why did the serpent set out to destroy their paradise?

It is not uncommon for someone who can’t hurt an enemy to hurt someone close to their enemy instead.

Mankind’s battle between good and evil may have started in the Garden of Eden – Eve biting the apple and Adam following suit – but the real battle started before that, with Satan’s revenge campaign against God.

Even before Abraham became the first Jew, the conflict was there.

As US commentator Dinesh D’Souza puts it, “Plan A was to overthrow God. When that failed, Plan B was implemented – find the things that God cares about and ruin them instead.”

The Magnificent Seven

The 2026 State election has been officially called, and I am pleased to report that six other political parties have pledged their support to the Australian Family Party.

None of the following parties are running in this election – all are supporting our campaign:

“I am pleased to announce that People First is supporting the Australian Family Party at the forthcoming SA election.

If we want government to be for the people, then it has to be by the people.

Building a strong grassroots movement is vital if we are to make that happen.

It is our intention to formally merge our two parties after the election.”—Gerard Rennick, President, People First Party

“The HEART Party is proud to endorse and support the Australian Family Party in the South Australian State Election on 21 March 2026.

As a party committed to Health, Accountability, Transparency, Individual Rights, Environmental stewardship, and a strong, thriving Economy, we believe the Australian Family Party reflects these shared values and is well placed to represent them in the South Australian Parliament.

As the HEART Party is not contesting this election, we strongly encourage our members, supporters, and all South Australians who share our values to cast their vote for the Australian Family Party.”—Michael O’Neill, President, HEART Party

“South Australian Election–DLP Supports Australian Family Party.

South Australian DLP members and supporters and others who are committed to traditional Christian values are urged to vote for the Australian Family Party in the state election on Saturday 21 March 2026.”—Richard Howard, National Secretary, DLP

“So many smaller parties getting behind Bob Day’s Australian Family Party is magnificent! It is a testimony to both Bob’s standing in the political realm, and the Australian Family Party’s genuine pro-Australia, pro-South Australia policies.”—Rodney Culleton, Party Leader, Great Australian Party

“We are committed to supporting the Australian Family Party at the upcoming South Australian State Election.”

Whatever we, as a party, can do – including encouraging our members to support the Australian Family Party at pre-polls, polling booths, scrutineering and more – we will do.”—Glenn O’Rourke, National Director, Australian Federation Party

“The Libertarian Party SA is proud to formally endorse Bob Day for the upcoming South Australia state election on March 21. Bob brings a wealth of experience and a tireless commitment to individual liberty, free markets, and limited government”.—Libertarian Party SA

The Australian Family Party will be running candidates in every Lower House seat (47 in total) plus three in the Legislative Council – a total of 50 candidates.

With One Nation grabbing most of the headlines and the Liberals in disarray, SA’s Labor Premier Peter Malinauskas is now in an awkward position.

He has enjoyed extremely high personal approval ratings since becoming Premier and a 2025 YouGov poll showed the Premier’s net satisfaction rating at +70, a phenomenal number. Labor’s two-party preferred was also a whopping 67–33!

Malinauskas has dominated the news cycle with his ‘bread and circuses’ strategy of big-name events such as golf tournaments, beach volleyball competitions, motor sport carnivals and Katy Perry-type concerts.

Over recent months, however, a number of more substantial policy areas have begun to chip away at the Premier’s seemingly impenetrable veneer.

A toxic algal bloom has blighted the South Australian coastline and shows no sign of disappearing any time soon. His government is copping much of the blame for not acting when the bloom was first reported.

His key 2022 election promise to ‘fix ambulance ramping’ has not been fulfilled – in fact, ambulance ramping is worse now than it was in 2022!

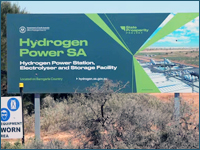

State taxpayers are expected to lose $500 million on his government’s green hydrogen debacle.

State debt is climbing towards $50bn and South Australia, once considered the nation’s home-ownership capital, is now ranked the 2nd least affordable in Australia!

And he has introduced legislation into the South Australian parliament enshrining an Aboriginal Voice, despite South Australians voting overwhelmingly ‘No’ in the Voice referendum.

All of these add up and eventually reach a tipping point.

That tipping point could well be election day.

Can you help?

Are you available to do some letterboxing in your area or hand out some how-to-vote cards for us on election day – or better still, at early polling stations? If so, please contact us here.

Thank you for your support.

Authorised by Bob Day, Australian Family Party, 22 Grenfell Street, Adelaide SA 5000

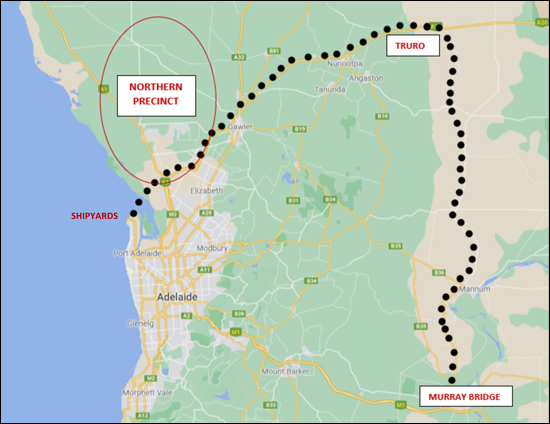

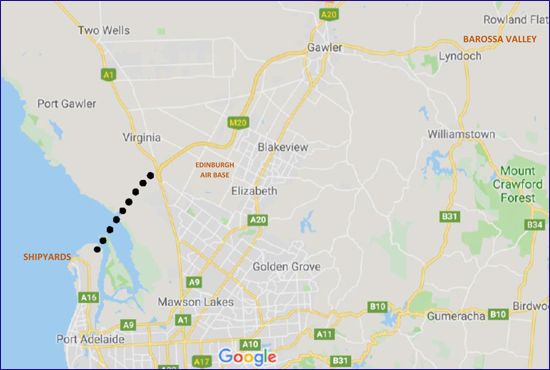

Adelaide’s north can provide the land, and a new world-class gateway bridge over the Port River can connect the naval precinct with the northern Adelaide plains. Such a bridge and road system – perhaps even a rail line down the middle – would provide essential access to housing, supply chains and tourism opportunities – not to mention a ten-minute drive from the Edinburgh military air base.

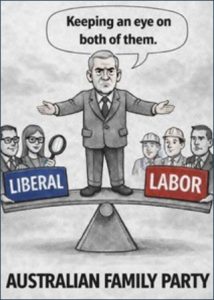

Adelaide’s north can provide the land, and a new world-class gateway bridge over the Port River can connect the naval precinct with the northern Adelaide plains. Such a bridge and road system – perhaps even a rail line down the middle – would provide essential access to housing, supply chains and tourism opportunities – not to mention a ten-minute drive from the Edinburgh military air base. First coined by the Roman poet Decimus Junius Juvenalis, ‘Who guards the guardians?’ is a question that has been invoked throughout the past two thousand years – most notably in the Magna Carta of 1215 and the US Declaration of Independence of 1776.

First coined by the Roman poet Decimus Junius Juvenalis, ‘Who guards the guardians?’ is a question that has been invoked throughout the past two thousand years – most notably in the Magna Carta of 1215 and the US Declaration of Independence of 1776. In South Australia, the Labor Government is spending somewhere in the vicinity of $50m on political advertising dressed up as ‘community information’.

In South Australia, the Labor Government is spending somewhere in the vicinity of $50m on political advertising dressed up as ‘community information’. In Act 1 of Shakespeare’s great play Macbeth, the three witches appear before Macbeth and his friend Banquo. The witches predict that Macbeth will be king, and that one of Banquo’s sons will also be king one day.

In Act 1 of Shakespeare’s great play Macbeth, the three witches appear before Macbeth and his friend Banquo. The witches predict that Macbeth will be king, and that one of Banquo’s sons will also be king one day. Christmas story No. 1:

Christmas story No. 1: In a much-quoted exchange, a pollster once asked an Australian voter the following question: “Going into this election, and thinking about the average voter, what would you say is the biggest problem facing Australia today – ignorance or apathy?”

In a much-quoted exchange, a pollster once asked an Australian voter the following question: “Going into this election, and thinking about the average voter, what would you say is the biggest problem facing Australia today – ignorance or apathy?” Standing Guard

Standing Guard It’s been said that ‘Optimists learn English, pessimists learn Chinese, and realists learn how to use an AK47.’

It’s been said that ‘Optimists learn English, pessimists learn Chinese, and realists learn how to use an AK47.’ Four incidents converged recently – two from Western Australia and two from South Australia.

Four incidents converged recently – two from Western Australia and two from South Australia. When John D. Rockefeller died in 1937, he was reputedly the richest man in the world.

When John D. Rockefeller died in 1937, he was reputedly the richest man in the world.