An Australian was on holidays in the south of France.

An Australian was on holidays in the south of France.

Strolling along outside his hotel, the Aussie was suddenly attracted by the screams of a young woman kneeling in front of a small child.

The Aussie knew enough French to determine that the child had swallowed a coin.

Seizing the little boy by the heels, the Aussie held him up and gave him a few good shakes and out popped the coin.

“Oh, thank you sir, thank you,” cried the woman.

“You seemed to know just how to get that coin out of him, are you a doctor?”

“No madam,” replied the man, “I’m with the Australian Tax Office.”

In a previous post, Prison Break, I spoke of rights and responsibilities.

Regulations that prevent people from working under terms and conditions which suited them was, I said, an infringement of liberty, freedom and dignity. It violated a person’s right to get a job and their responsibility to provide for their families.

I will now add a further hazard – it prevents them from paying tax to cover the many services the state provides to them.

Rights … responsibilities … and tax. They are all linked.

Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Finance Minister to King Louis XIV of France, famously declared that “The art of taxation consists in so plucking the goose as to obtain the largest possible amount of feathers with the smallest possible amount of hissing.”

A modern finance minister might rephrase this as, “The largest possible amount of revenue with the smallest possible amount of economic and political damage.”

Which brings me to a man called Arthur Laffer.

I had the privilege of meeting the famous US economist in Parliament House in 2015. Dr Laffer was in Australia on a speaking tour.

Arthur Laffer is of course most famous for his Laffer Curve.

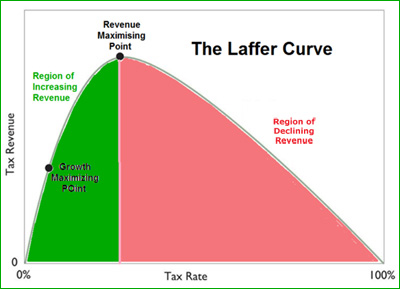

It is self-evident that tax revenue would be zero if tax rates are set at 0 per cent (bottom left corner of the graph).

Revenue would also, of course, be zero if rates were set at 100 per cent, as there would be no incentive to work! (bottom right corner).

Starting at 0 per cent, as tax rates rise, revenue rises until, at some point on the graph, revenue starts decreasing as it heads towards that 100 per cent point.

Eminent Australian and UK economist Colin Clark once said economic growth declines if taxation is more than 25 per cent of GDP.

It’s also been said, “When the taxes of a nation exceed 20% of the people’s income, there is a lack of respect of government. When it exceeds 25%, lawlessness.”

In Australia it is close to 30 per cent.

Take one example of this lawlessness – the black economy – currently estimated at 15 per cent of GDP, one of the largest in the developed world. An underground economy of that magnitude requires the involvement not only of a lot of businesses, but also of millions of consumers.

As we know, laws only work when people believe in them and, clearly, they have no respect for our tax laws.

Despite what many advocating tax increases would have us believe, the total tax take in Australia is quite high. They say that compared with other developed economies, Australia is a low tax country, and that workers and companies could comfortably pay more. Not so.

When it comes to taxing incomes, Australia is up there with the Europeans and is way ahead of most of our neighbours in the Asia–Pacific region.

A paper published by the Adam Smith Institute stated, “If you look at the experience of those who have introduced a single-rate flat tax, and also the tax reforms of the 1980s which took place in Britain and America, reducing tax rates causes revenues to rise.”

As Arthur Laffer has found, and as has been demonstrated many times, when taxation rates are reduced, revenues do not fall. When the Australian company tax rate was cut from 39 to 30 per cent, revenues went up, not down. The famous Reagan tax cuts from 70 per cent to 30 per cent in the 1980s produced a $9 billion increase in revenue when a $1 billion shortfall had been forecast.

When Sweden halved its company tax rate from 60 per cent to 30 per cent, company tax revenue tripled.

Nobody enjoys paying taxes, but in the 1950s and 1960s, relatively low taxation and a comparatively simple set of tax rules meant that most people paid what was due without too much hissing, to quote Colbert.

Today, however, the Government and the ATO find themselves locked into a destructive relationship of repression and resistance with ordinary taxpayers.

Where people can avoid tax by exploiting loopholes, they will do so; where they can’t (eg, PAYG taxpayers), they become resentful at the unfairness of it all.