In his fascinating book, A Theory of Justice, the American moral, legal and political philosopher John Rawls promotes an idea called the Veil of Ignorance.

In his fascinating book, A Theory of Justice, the American moral, legal and political philosopher John Rawls promotes an idea called the Veil of Ignorance.

When drawing up laws, says Rawls, lawmakers should imagine themselves standing behind a curtain or veil, ignorant of what position they themselves will occupy once the law has been passed. Rawls cites a number of examples of this idea, the second being housing which I will cover shortly.

The first example he gives is in relation to slavery. What sort of law would lawmakers write if they were unsure whether they themselves would be slave or slave owner once the curtain was lifted?

His second example of housing is as relevant today as it was in 1970 when he wrote his ground-breaking book.

This approach, he states, would create a more just society.

Let’s consider this in relation to housing.

Knowing what they know now, how would today’s baby-boomers write housing and planning laws if they did not know, once the veil was lifted, whether they would be young or old?

In the event they found themselves in the ‘young’ category, it is beyond doubt they would want low-cost, low-entry level rules to get into their first home – as happened for them 40 years earlier!

As we know, low-cost, low-entry housing is not what first homebuyers are faced with in 2022. Entry-level housing is not three times the median wage like it was for previous generations. It is seven … eight … nine … even ten times the median income.

Regrettably, today’s laws are written more in the mode of ‘I’m alright Jack, pull the ladder up’ rather than, ‘What if I’m a young person trying to get a foot on the employment ladder or trying to buy a first home, or having to pay off a student loan?’

As previously described on this site, Australia does not have, and has never had, a ‘housing’ affordability problem. It has a ‘land’ affordability problem. The actual cost of building a house in Australia has kept pace with inflation and is low by international standards. The price of land on which to the build the house, however, has skyrocketed.

Land is the problem.

By restricting the amount of land available, lawmakers have sent the price of entry-level housing through the roof. Lawmakers have used urban planning laws to restrict the amount of fringe land available and have then drip fed it to a land-starved housing industry.

The ‘scarcity’ that drives up land prices is wholly contrived – it has been a matter of political choice, not geographic reality. It is the product of restrictions imposed through planning regulation and zoning.

Some of the claims used by lawmakers to stop urban growth are that urban growth is not good for the environment, or that it prevents the loss of agricultural land, or that it saves water, or it leads to a reduction in motor vehicle use or it saves on infrastructure costs for government. Although all of these claims are either false and/or misleading, they have become accepted wisdom. Few have had the courage or the insight to challenge them.

One of those few is Patrick Troy.

In his 1996 book The Perils of Urban Consolidation, Patrick Troy, Emeritus Professor at the Australian National University, and a leading thinker on urban planning, squarely challenged the assumptions on which the urban densification principles are based. He pointed to flaws in the figures and arguments which have been used over and over again to support what is speciously called ‘smart growth’ arguing that these policies will produce ‘mean streets’, not ‘green streets’.

Until the 1970s, the development of new suburbs was largely left to the private sector. The many leafy, liveable suburbs like Netherby or Colonel Light Gardens south of Adelaide or Tea Tree Gully in the north-east with their large allotments and wide streets are an enduring testimony to what suburbs looked like before planning laws were introduced. Compare these old suburbs with the packed-like-sardines stuff foisted on young home-buyers today!

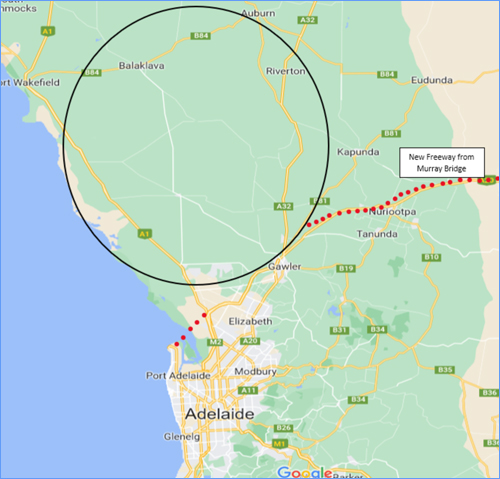

In last week’s Newsletter, we discussed opening up Adelaide’s northern plains to provide access to housing, employment, supply chains and tourism opportunities for the new $100bn maritime defence project based at North Haven.

The northern Adelaide plains are more than three times the size of metropolitan Adelaide – a city of over a million people that has taken over 150 years to get to where it is today. There is enough land in Adelaide’s north to last for centuries.

To enable first home-buyers easy access to housing – on quarter acre (1,000 sq metre) blocks if they want to kick a ball around and/or grow a few vegies, fruit trees and chickens – for around $300,000 and to permanently fix the ‘land’ problem, ensuring future generations do not have to suffer a similar fate, we need to do five things:

- Where they have been applied, urban growth boundaries or zoning restrictions on the urban fringe must be removed. Residential development on the urban fringe needs to be made a ‘permitted use’.

- Compulsory ‘Master Plan’ communities need to be abolished. If large developers wish to initiate Master Planned Communities, that’s fine, but don’t make them compulsory. This will allow smaller developers back into the market.

- Allow the development of basic serviced allotments – ie, water, sewerage, electricity, stormwater, bitumen roads, street lighting and street signage. Additional services and amenities – such as lakes, entrance walls, childcare centres, bike trails, etc – can be optional extras if the developer wishes to provide them and the buyers are willing to pay for them.

- Privatise planning approvals. Any qualified Town Planner should be permitted to certify that a development application complies with a Local Government’s Development Plan.

- Abolish up-front infrastructure charges and so-called ‘developer contributions’ by Local or State Governments. All infrastructure services should be paid for through the rates system – ie, pay ‘as’ you use, not ‘before’ you use – like it was for the boomers! First home-buyers should not be singled out and forced to pay up-front for Local or State Government infrastructure expansion given that existing homeowners were not required to contribute when they bought in.

Thank you for support.