How governments have:

How governments have:

- Cruelled the housing aspirations of millions of low and middle income households

- Disempowered and impoverished families and individuals

- Entrenched intergenerational inequity

- Weakened free enterprise, property rights, economic freedom and individual liberty; and

- Like China’s One Child Policy, set ticking a time bomb that will cause a catastrophic social and economic burden for future taxpayers

OVERVIEW

House prices matter. A lot.

In the 18 years since the new millennium, the median house price in most large American/Canadian/British/Australian/New Zealand (ACBANZ) cities has risen from an average three times median income to more than six times median income and in some cities more than nine times median income. That is, in real terms, allowing for inflation, a doubling, and in some cases a tripling, of the cost of housing.

At six times median household income a family will be required to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars more of their money on mortgage payments and local government shire council rates, land taxes and stamp duty based on property values, than they would have, had house prices remained at three times the median income. That’s hundreds of thousands of dollars they are not able to spend on other things – clothes, cars, furniture, appliances, travel, movies, restaurants, the theatre, children’s education, charities and many other discretionary purchase options.

The distortion in housing markets and the misallocation of resources is enormous by any measure and affects every other area of a nation’s economy. New home owners pay a much higher percentage of their income on house payments than they should and renters pay increased rental costs as a result of the higher capital and financing costs paid by landlords.

The capital structures of these nations’ economies have been distorted to the tune of hundreds of billions of dollars and for those on middle and low incomes the prospect of ever becoming homeowners has all but vanished. The social and economic consequences of this change will be these nations’ equivalent of China’s disastrous One Child Policy.

The consequences are as profound as they are damaging and getting things back into alignment is going to take some time. But it is a realignment that is necessary. A terrible mistake was made and it needs to be corrected.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- History of home ownership

- The West’s ‘One Child Policy’ – the consequences of high housing costs

- The immutable laws of supply and demand – the causes of high housing costs

- Red tape, green tape, housing taxes, zoning taxes, development charges

- Free enterprise, property rights, economic freedom and individual liberty

- International comparisons

- Recommendations – what to do and what not to do

1. History of home ownership

Home ownership has long been a feature of ACBANZ life. During the 50 years following World War II, levels of home ownership rose steadily from around 50 per cent in 1945 to over 70 per cent by 1995. Home ownership had become both a symbol of the equality ACBANZ families shared, and a means through which an average family could provide security and stability while building wealth and claiming a tangible stake in their nation. For the vast majority, owner-occupation of the home in which they live was, and remains, a great ambition.

This aspiration, so deeply entrenched in the national psyche, was perfectly described by Australian Prime Minister Sir Robert Menzies in his “Forgotten People” address of 1942. He recognised the moral, social and emotional importance of the family home:

“The material home represents the concrete expression of saving ‘for a home of our own’. Your advanced socialists may rage against private property (even whilst they acquire it); but one of the best instincts in us is that which induces us to have one little piece of earth with a house and a garden which is ours, to which we can withdraw, in which we can be among our friends, into which no stranger may come against our will.”

Prime Minister Menzies understood that the human instinct to build and bequeath a home, sent lasting ripples through every aspect of social and economic life.

Extensive national and international research confirms what we intuitively know, namely, that home owners have better health than their renting peers and children from low income families who live in a home owned by their parents, do better than children from low income families who live in rented accommodation. Home owners have a tangible stake in their community. They live where they choose and for as long as they choose. Unlike renters, they do not face the prospect of having to pack up the family and move on at the expiration of a lease. Nor do they face ever-increasing rents for a property in which they will never have a stake. Home owners have greater self-confidence, they move less frequently, they are more involved in their communities, and their children are also more likely to become home owners. In addition, they have significantly greater wealth and, in communities where home ownership levels are high, crime is lower, household incomes are higher and some studies even show divorce rates to be lower. “Emotional security, stability, and a sense of belonging” are listed as the top reasons for home ownership followed by “financial security and investment”.

In recent years however, a disturbing trend has emerged in the level of home ownership among young families. It is in substantial decline. Whilst those who bought into the housing market before 1999 when prices were low have done well, those who bought after 1999 have had to take out big mortgages in order to enter the market.

2. The West’s ‘One Child Policy’ – consequences of high housing costs

A disturbing socio-economic shift is occurring. A schism, a rupture, creating a new ‘haves and have nots’ split between largely older existing home owners who as a result of soaring property prices have accumulated significant wealth, and younger, would-be home owners. Housing is being consolidated into the hands of fewer and fewer people. Homelessness is growing. And as populations grow, the situation is worsening. Low income people – young people in particular, are spending a much higher percentage of their income – up to 50%, on housing costs than previous generations at the same age, and the number of young people in rental accommodation has doubled. The number of years to pay off a home loan has increased dramatically and the number of people who are ‘mortgage free’ by age 50 has halved. And the number of first home buyers receiving assistance from family and friends has doubled since the 1970s.

As high housing costs raise the cost of living and reduce the standard of living, places which have the highest housing costs eg California, also have the highest poverty rates.

Low income households in particular have been disproportionately affected by the rise in house prices. Their spending on housing as a percentage of their income has risen significantly more than households in higher income brackets.

The severity of the problem is also being masked by low interest rates. An interest rate rise would be catastrophic for the many home owners who have borrowed huge sums in order to enter the market highlighting the danger of measuring affordability, as some do, by the capacity to meet mortgage payments, rather than the total amount owed.

In creating the conditions for housing to become the privilege of the few rather the rightful expectation of the many, governments have produced intergenerational inequity and breached the moral contract between generations which dictates that we should leave things better than we found them.

In making housing much less affordable for the next generation it has denied them much more than a roof over their heads, it has denied them the security and benefits that go with home ownership and the opportunity to provide options for themselves in later life.

Those who own their homes have much more control over their lives. They can choose where they will live and how they will live. Many are now choosing to defer having a family in the hope that they will be able to somehow put together the funds to buy a home later in life. If they can’t afford to buy a house they reason, they certainly can’t afford to have children.

With changing demographics – the number of taxpayers supporting non-taxpayers, it is imperative that as many citizens as possible own their homes by the time they retire. Aged pensions were not designed to cover mortgage or rent payments. National governments who are responsible for aged pensions, and future taxpayers will have a massive problem on their hands.

This massive escalation in the price of housing carries with it a multitude of detrimental impacts. Establishing affordable rental accommodation for those in greatest need becomes even more difficult for social and public housing authorities as they seek to purchase land and houses in a greatly inflated market. Road widening and major infrastructure projects experience cost blow-outs as land acquisition costs skyrocket, and establishing schools, community centres, health services and business facilities becomes difficult, and at times impossible. The whole community suffers as a result of increased tax, transaction, finance and establishment costs.

High house prices also distort labour markets. Cities would benefit greatly if people could afford to live in them. Instead they live elsewhere depriving cities and creating labour shortages.

German economists are said to be baffled by reports that rising house prices in many western countries are deemed to be ‘good news’. In Germany, inflation in house prices, like inflation in energy prices or food prices, are considered just the opposite. How can it be “good news”, they ask, when it now takes two incomes to support a mortgage when previously young couples could buy a home and raise a family on one? Or that a homebuyer will pay many hundreds of thousands of dollars more in mortgage payments and government taxes and charges than would otherwise be the case?

The answer of course is not economics but politics. As house prices rose dramatically in recent years, political parties reaped the political benefits. Voters felt richer. But this is now backfiring. High house prices are no longer viewed as a political asset but a liability – particularly for conservative or right-of-centre parties which have traditionally embraced home ownership as an article of faith. A policy space they once owned now represents a real and present danger. They are in danger of being judged by their electorates as having failed. Like the prisoner on death row whose imminent demise ‘focuses the mind’, the politics of housing affordability is putting the political class on notice. Governments which trumpet a $1,000 a year tax cut are failing to do anything about a $10,000 a year increase in mortgage costs.

China’s ‘Great Wall of Family Planning’ was one of the boldest policies any nation has implemented. However, 35 years on, the policy’s disastrous effects are becoming more and more evident. The policy has upended traditional structures for supporting older generations and caused social unrest that will be felt for decades to come.

The Chinese government has since acknowledged the disastrous social consequences of the gender imbalance as a result of its one child policy. The shortage of women has increased mental health problems and socially disruptive behaviour among men, and has left many men unable to marry and have a family. The scarcity of females has resulted in kidnapping and trafficking of women for marriage and increased numbers of commercial sex workers, with a potential resultant rise in human immunodeficiency virus infection and other sexually transmitted diseases. There are fears that these consequences could be a real threat to China’s stability in the future.

Housing is slowly undermining western economies like China’s policy is undermining its social demographic structure. It is a massive government-mandated constriction of supply – not of citizens but of houses.

China has abandoned its policy mistake. The west needs to do the same before it passes the point of no return.

3. The immutable laws of supply and demand – the causes of high housing costs

It was once the case that if a person, or indeed a country, knew how to make something, the world would beat a path to its door. The factories and mills of 19th Century England bore witness to the power of being able to make things. Britannia ruled the waves. Today, manufacturing is global. From motor vehicles to whitegoods, kitchen appliances to widescreen TV sets, personal computers to cell phones, the world is awash with supply – and demand. And yet despite this ever-increasing demand, prices continue to fall.

Despite numerous dire warnings over the past 200+ years – most notably Thomas Malthus’ 1798 book ‘An Essay on the Principle of Population’, predicting population growth would eventually exceed food production resulting in famine and starvation, even global food supply continues to exceed demand by a considerable margin.

So why does housing – a simple manufactured product, defy this trend? Why does a house, which like other manufactured goods contains readily accessible components, increase in price out of all proportion to other consumer products?

Under normal market conditions, when demand increases, prices rise and markets respond with increased supply thereby reducing prices.

Demand stimulators like immigration, low interest rates, favourable tax treatments and first home buyer grants have unquestionably increased demand for housing. However increases in demand do not, of themselves, cause prices to rise. The exponential increases in demand for cell phones, laptops and plasma televisions in the first decade of the new century for example did not lead to increases in price. In fact the opposite occurred – prices fell, in some cases by more than half, due to increases in supply of these goods. The post-war population explosion ‘baby boom’ was matched by increases in housing supply but house prices barely moved.

So what has gone wrong?

On the fringes of most cities there is a more than adequate supply of cheap land available and housing industries ready, willing and able to put good quality houses on it at competitive prices.

So why are houses not being built on this cheap land? Cheap land attracts not only home buyers but commercial interests as well, leading to enhanced employment opportunities.

Whenever there is money to be made, opportunities to do business with governments present themselves – particularly in tightly controlled markets like land. Relationships between business people and governments are as old as regulation itself.

What can give these relationships real potency however is what’s been called the ‘Baptists and the Bootleggers’ phenomenon. The term stems from the Prohibition days, when members of the US government received private donations from Bootleggers – rent-seeking business people eager to maintain a scarcity (and resulting high price) of their product (alcohol). These same Members of Congress then justified maintaining the prohibition by publicly adopting the moral cause of the Baptists who were extolling the evils of the product.

So it is with land development. Political parties are lobbied by and receive donations from property developers keen to maintain the scarcity of the product (zoned land), which results in higher property prices. The members of parliament then get on the property-owning bandwagon themselves and, keen to maintain their own new-found wealth, publicly support urban planners who continually rail against the so-called evils of ‘urban sprawl’, none of which stands up to scrutiny. The resulting urban growth boundaries which restrict home building activity through zoning laws, force new home buyers into high density housing developments downtown (CBD) and in inner suburbs, and are a classic example of the Baptists and the Bootleggers phenomenon at work – the monetisation of urban planning. Property bootleggers often respond by saying more fringe land does not need to be rezoned (from low value rural to high value residential) because “there is 15 years supply of (high value) zoned land available” – owned by them of course. Price is not mentioned. At current prices, the land may well take 15 years to sell. Price matters. If they doubled the price they would have 30 years of land available, as that’s how long it would take to sell. If they halved the price the land would be sold in less than 2 years. The price difference between land zoned for housing and land not zoned can be as much as 100 times. The incentive for land owners to engage in everything from misconduct to outright corruption is immense in pursuit of either the windfalls available in the case of owners of unzoned land, or to maintain asset values in the case of those holding large tracts of zoned land.

Claims that urban sprawl is bad and that urban densification or urban consolidation is good for the environment, or that it stems the loss of agricultural land, or that it encourages people onto public transport, or that it saves water, or that it leads to a reduction in motor vehicle use or that it saves on infrastructure costs for government are false. Urban consolidation is an idea that has failed all over the world. Whether it’s traffic congestion, air pollution, the destruction of bio-diversity or the unsustainable pressure on electricity, water, sewage, or stormwater infrastructure, urban densification has been a disaster. Urban consolidation is not good for the environment, it does not save water, it does not lead to a reduction in motor vehicle use, it does not result in nicer neighborhoods, it does not stem the loss of agricultural land, it does not save on infrastructure costs for government and worst of all it puts home ownership out of the reach of those on low and middle incomes. Sir Peter Hall of the London School of Economics claims, “The biggest single failure of urban densification has been affordability.”

This limiting of housing on the urban fringes of cities distorts the inner suburban market where the ‘Save our Suburbs’ groups – committed to maintaining the character of existing suburbs by limiting the amount of additional in-fill housing, are highly effective. This further exacerbates the supply/demand distortion.

And it’s not as if high rates of construction of high density housing apartments – a favourite of urban planners, leads to improved housing affordability. Sydney, Toronto and Vancouver which have seen very high rates of high rise apartment construction are among the worst cities in the world in terms of affordability. Here again, planning restrictions limiting the number of apartments per site in the form of height restrictions add hundreds of thousands of dollars to the cost of an apartment. In Sydney for example, the average construction cost of a high rise apartment is $430,000 whereas the sale price is over $800,000.

And it is young home buyers, hit with the spiralling costs of home ownership who end up paying. Whilst it is true there has been an increase in younger people preferring downtown (CBD) apartment living, they are mostly forced into these overpriced units without being given the choice of a low cost, free-standing home of their own on the fringe. Given the price distortions inherent in today’s housing market, it is impossible to know what the trade-off points might be between downtown living, size of home, large backyard, children, pets, and suburban living.

Given housing is such a political hot potato, governments have responded. But unlike ‘the war on drugs’ where governments’ primarily focus on trying to limit supply, with housing, the overwhelming response by governments has been calls to limit demand – lower levels of immigration, the removal of favourable taxation treatments – negative gearing and capital gains tax discounts and bank lending restrictions.

These are merely window dressing, and, together with measures like changes to self-managed superannuation fund rules, pension rules, first home owner grants, shared equity schemes, social/public/community housing projects, deposit saver accounts, stamp duty exemptions for people down-sizing, congestion taxes, land taxes, negative gearing, capital gains tax, bank lending restrictions (eg requiring banks to have less than 30% of loans as ‘interest only’) they are totally ineffectual at solving the affordability problem.

4. Red tape, green tape, housing taxes, zoning taxes, development charges

Planning controls, development restrictions, environmental regulations, multiple jurisdictions, minimum lot sizes, lengthy approval processes, ‘developer’ contributions, ‘affordable housing’ requirements on new housing developments … building a house is no longer a simple matter. What has for centuries been an uncomplicated industry has become mired in planning rules and regulations which have sent prices skyrocketing. Restrictive planning rules – effectively housing taxes, now account for up to 50% of the cost of a house.

Traditionally, actual land costs have been no more than 20% of the total cost of a house and land package. Average construction costs have also been fairly consistent across most jurisdictions at approximately $1,000 per square metre or $100 per square foot, a figure that has changed little in over 30 years. This equates to an average construction cost of a 150 square metre or approximately 1,500 square foot starter home of $150,000. Likewise land development costs – roads, water, sewage, power, telecommunications, footpaths and street signage, across most jurisdictions are consistently around $40,000 per lot. Add profit margin and raw land costs of $10,000 per lot for a total house and land of $200,000

– three times median incomes. In places where there is light planning regulation, new homes can be purchased for this price. In places where there is heavy planning regulation, new homes are more than double this price.

The affordability of housing is overwhelmingly a function of one thing – the extent to which governments impose rules and regulations over the construction of houses and land allotments.

In essence, what has been described as a ‘housing affordability’ problem is simply a ‘land affordability’ problem.

Ludwig von Mises, one of the most notable economists and social philosophers of the twentieth century, made a striking observation about those who seek to exert their planning influence on the lives of ordinary people:

“The planner is a potential dictator who wants to deprive all other people of the power to plan and act according to their own plans. He aims at one thing only: the exclusive absolute pre-eminence of his own plan.”

Most urban planning can be traced back to the UK’s 1947 Town & Country Planning Act. For the past 70 years this template has been an enduring testimony to both the folly of government bureaucratic interference and the dogged and blind adherence to a flawed dogma.

Over 70 books are currently in print on government policy failures– from World War 1 to the space shuttle disasters to the global financial crisis and associated credit rating fiascos to foreign policy disasters. These include ‘The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914’ (Clark); ‘The Blunder of our Governments’ (Crewe & King); ‘Understanding Policy Fiascos’ (Bovens & ‘t Hart); ‘Not Steering but Drowning: Policy Catastrophes and the Regulatory State’ (Moran); and of course, Sir Peter Hall’s ‘Great Planning Disasters’. In his book, ‘American Nightmare: How Government Undermines the Dream of Homeownership’, Randall O’Toole, one of America’s leading public policy analysts, documents example after example of government planning failures. He demolishes the widely held belief that government planners are somehow smarter or more capable of managing the future than market forces. “Better to fire the planners and let free people, free minds and free markets use the genius of their freedom”, he says.

Where the free market kept house prices affordable for the best part of a century, government interference and price fixing has done the opposite.

Even the 2008 Global Financial Crisis had its origins in the interference of the Clinton and Bush administrations, by instructing banks to extend mortgages to low-paid and minority Americans who were unable to afford them.

Why were people unable to afford homes when the cost of building was low? And, why did the sub-prime crisis affect some States in the US but not others?

The answer to these questions goes to the heart of government failures – central planning, in this case urban planning controls.

These can be traced back even further than Clinton and Bush to Franklin D Roosevelt and his National Housing Act (1934).

The 1934 Act began the practice of lending to minority groups and people on low incomes. The market at the time responded to this government interference with a practice called ‘redlining’ whereby certain areas on maps were identified as being ‘high risk’. This then led to the enactment of the Fair Housing Act of 1968 and subsequently Jimmy Carter’s 1977 Community Reinvestment Act.

Following this came Clinton’s ‘Community Development Financial Institutions Act’ and ‘Low Income Housing Tax Credit’ program of 1994 in which the Clinton Administration pressured US banks and mortgage companies to relax their lending criteria so that minority groups and those on low incomes could buy more houses. At one point, 40% of financial institutions’ loans were to low income people.

What triggered the catastrophe of 2008 however was the added components of ‘new urbanism’ or ‘smart growth’ urban planning laws in many of the large housing markets of the US -California and Florida, in particular, and ‘non-recourse loans’ or ‘jingle mail’ – if a property dropped in value below the amount owing to the bank, the homeowner could simply walk away from the property without being liable for the banks’ losses. The owner simply mailed the keys to the bank, hence the term ‘jingle mail’.

During the 1990s house prices in these highly regulated states rose dramatically on the back of an ‘everything to gain, nothing to lose, non-recourse loan’ mentality and ‘new urbanism’ which severely restricted the supply of land on the urban fringes of many American cities. This was not the case however in low planning regulation states like Texas and Georgia.

The combined effects of mandated lending to low income groups and non-recourse loans together with skyrocketing house prices caused by planning regulations and restrictions in land supply presented lenders with a serious dilemma. Their mandated low income customers could not afford the repayments, so all sorts of financial products were developed

– sub-prime loans and mortgage insurance schemes (derivatives).

As has been sorely realised, anything not based on economic reality is doomed to failure. Sub-prime loans and mortgage insurance derivatives were not economic reality. The fallout sent shock waves across the globe.

After the GFC, headlines like Time Magazine’s, “Home Ownership has let us down” and the Wall Street Journal’s, “Poor better off renting” missed completely the cause of the problem.

5. Free enterprise, property rights, economic freedom and individual liberty

“The poorest man may in his cottage bid defiance to all the force of the Crown. His cottage may be frail; its roof may shake; the wind may blow through it; the storms may enter, the rain may enter—but the King of England cannot enter. All his forces dare not cross the threshold of the ruined tenement.” –William Pitt, British House of Commons 1763

Without property rights there can be no freedom.

Peruvian economist and author of ‘The Mystery of Capital’, Hernando de Soto, has shown property rights and property ownership have provided a foundation for the development of nations to the benefit of ordinary citizens:

“Legal property gave the West the tools to produce surplus value over and above its physical assets. Whether anyone intended it or not, the legal property system became the staircase that took these nations from the ‘universe of assets’ in their natural state to the ‘universe of capital’ where assets can be viewed in their full productive potential.”

The economic and personal security that comes from investing in your own home delivers, over time, a reduced housing cost and the wide range of future choices that come with having a valuable and tradable asset.

Home ownership gives citizens the asset means to start a business or put children through university. It must not be taken away.

Jane Jacobs, in her book ‘The Life & Death of Great American Cities’ observes, “An economy, if it is to function well, is constantly transforming poor people into middle class people. Planning should cause people to be better off, not worse off.”

Since the industrial revolution, people in developing countries have been flocking to the cities in search of a better life. And whereas in the 18th, 19th & 20th Centuries, cities and suburbs grew to accommodate the influx and working class people became middle class people, 21st Century governments are denying those on low incomes those same opportunities.

Restrictive planning laws take away property rights. They deny land owners the right to develop their land and in doing so disempower families and individuals and empower governments.

Matthew O’Donnell, from the Centre for Independent Studies in Australia states, “The greatest of all forms of spontaneous order is the market system itself. Every day goods and services are bought and sold by the millions without any central planner pulling the strings. It is truly wonderful how our daily needs are met with no one having any semblance of overall control. The burgeoning wealth of capitalist societies compared to the failure of every central planned socialist state confirms that the market system more efficiently allocates society’s resources than any consciously designed system could ever hope to.”

It is the role of government to prevent – certainly not encourage, the enrichment of one group at the expense of another. Impoverishment of one group will eventually lead to the impoverishment of every group. Through housing we are witnessing this first hand.

Housing has gone from a relatively free market to one controlled by rent-seekers and regulators.

The rising generation should not be denied a home of their own merely to satisfy the ideological fantasies of urban planners and the financial interests of rent-seekers. The parents of the rising generation should not be denied the joys of grandchildren because young couples have to work to pay mortgages instead of raising a family. The joke that high mortgages are the new contraceptive is becoming no laughing matter. Young women used to be afraid of getting pregnant, now, as they approach 40, they are afraid of not getting pregnant. Couples should be able to pay off a home loan on one income so they can start a family in their late 20s, not in their late 30s or early 40s.

6. International comparisons

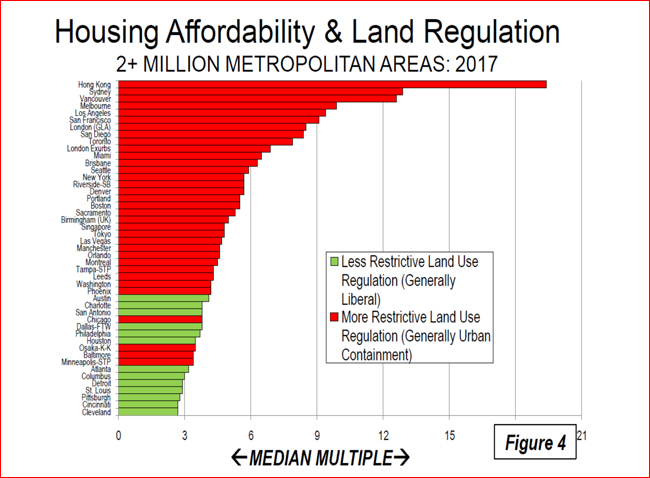

When making international comparisons of housing affordability, it is instructive to compare not just countries but cities, states and provinces within those countries. Housing affordability varies markedly within countries in direct relation to particular cities’ urban planning policies. The disparity within some countries is significant. For example, in Canada’s British Columbia province, Vancouver has a house price to income ratio of 12.6 (the median house price is 12.6 times the median household income) whereas the city of Edmonton in Alberta province has a house price to income ratio of 3.7. In the United States, cities in California – Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Jose and Santa Cruz all have house price to income ratios over 9.0 whereas Cleveland and Cincinnati (Ohio), Oklahoma City (Oklahoma) and St Louis (Missouri) all have house price to income ratios of under 3.0.

International studies show unquestionably a direct correlation between land use regulation and housing affordability – where there is more regulation, houses are less affordable. Demographia’s Annual International Housing Affordability Survey www.demographia.com of nearly 300 housing markets in 9 countries compares house price to income ratios in each city and country.

“For metropolitan areas to rate as ‘affordable’ and ensure that housing bubbles are not triggered, housing prices should not exceed three times gross annual household earnings. To allow this to occur, new starter housing of an acceptable quality to the purchasers, with associated commercial and industrial development, must be allowed to be provided on the urban fringes at 2.5 times the gross annual median household income of that urban market. The critically important “development ratios” for this new fringe starter housing should be 17 23% serviced lot/section cost -the balance the actual housing construction. Ideally through a normal building cycle, the Median Multiple should move from a Floor Multiple of 2.3, through a Swing Multiple of 2.5 to a Ceiling Multiple of 2.7 -to ensure maximum stability and optimal medium and long term performance of the residential construction sector.” -Hugh Pavletich, Demographia Co-Author

In the US, 13 of the 54 major cities surveyed by Demographia are rated as severely unaffordable; in the UK the ratio is 6 out of 21; in Canada 2 out of 6; in Japan, of the two cities surveyed – Osaka/Kobe/Kyoto and Tokyo/Yokohama, Osaka/Kobe/Kyoto has a price to income ratio of 3.5 and Tokyo/Yokohama has a ratio of 4.8. In Singapore the ratio is 4.8, in Ireland, Dublin has a ratio of 4.8 – up from 3.3 in 2011, Galway 4.0, Cork 3.7. Waterford 2.7 and Limerick 2.2. are rated affordable Irish housing markets.

All of Australia’s major markets have urban containment policies and all have severely unaffordable housing – Sydney 12.9, Melbourne 9.9, Brisbane 6.6, Adelaide 6.3 and Perth 5.9.

Australia’s unfavourable housing affordability is in significant contrast to the 3.0 ratio which existed before the implementation of urban containment (urban consolidation/densification) policies.

All 3 of New Zealand’s major housing markets are rated as severely unaffordable – Auckland 8.8, Wellington 5.5 and Christchurch 5.4. Hong Kong has a severely unaffordable ratio of 19.4.

(Demographia’s 14th Annual International Housing Affordability Survey – reproduced with permission).

“Urban Containment Policy: In contrast with well-functioning housing markets, virtually all the severely unaffordable major housing markets covered in the Survey have restrictive land use regulation, overwhelmingly urban containment. A typical strategy for limiting or prohibiting new housing on the urban fringe an “urban growth boundary,” (UGB) which leads to (and is intended to lead to) an abrupt gap in land values. Contrary to expectations that higher densities would lower land costs and preserve housing affordability, house prices have skyrocketed inside the UGBs. This also leads to extraordinary price increases that attract investment (speculation), a factor that has little or no impact on middle-income housing affordability where there is liberal regulation (as opposed to urban containment).” – Wendell Cox – Demographia Co-Author.

According to the latest (2018) UBS Global Real Estate Bubble Index, Hong Kong, London, Sydney, Toronto and Vancouver are at the greatest risk of seeing a correction in their house prices.

“Price bubbles are a regularly recurring phenomenon in property markets. The term “bubble” refers to a substantial and sustained mispricing of an asset, the existence of which cannot be proved unless it bursts. But recurring patterns of property market excesses are observable in the historical data. Typical signs include a decoupling of prices from local incomes and rents, and distortions of the real economy, such as excessive lending and construction activity. The UBS Global Real Estate Bubble Index gauges the risk of a property bubble on the basis of such patterns. Vastly overvalued housing markets, as measured by the UBS Global Real Estate Bubble Index, have historically been associated with a significantly heightened probability of correction and greater downside than housing markets whose prices developed more in line with the local economy. This year’s (2018) UBS Global Real Estate Bubble Index publication reveals the cities in which caution is required when buying a house and the places in which valuations still seem fair. In this edition, Los Angeles and Toronto have been added to the selection of financial centres.” -UBS

Housing affordability has become not just a global problem but a global crisis.

As bad as the aforementioned countries are, the problem is growing faster in developing countries –India, the Philippines, Vietnam, Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, Central and South America.

Consistent studies show that between 75% – 80% of people across the world would like to own their own homes. And whilst the world is breaking out of poverty at a rate unparalleled in history – from 44% in 1981 to less than 10% in 2015, for the democratisation of wealth to continue, the housing road block must be removed.

7. Recommendations – what to do and what not to do

Regrettably, the general public is profoundly ignorant of the underlying causes of housing unaffordability.

Edmund Burke once said “It is the job of political leaders to teach people that which they do not know”.

Appealing to the political class alone to solve the housing crisis will not suffice. The public needs to be informed of both the causes of the problem and the solution. As former Australian politician Bert Kelly said of protectionism – once considered a settled public policy position, “trade protectionism needs to be made intellectually and morally disreputable.”

First, what not to do. As discussed above, policies which seek to suppress demand -lower levels of immigration, the removal of favourable taxation treatments – negative gearing and capital gains tax discounts, bank lending restrictions, changes to self-managed superannuation fund rules, pension rules, congestion taxes and land taxes, are futile. As are attempts by governments to assist home buyers with first home buyer grants, shared equity schemes, social/public/community housing projects, deposit saver accounts and stamp duty exemptions for people down-sizing.

As for what to do, first and foremost, where they have been applied, urban growth boundaries or zoning restrictions on the urban fringes of cities should be removed. Residential development on the urban fringe should be made “permitted use.” In other words, there should be no ‘zoning’ restrictions in turning rural fringe land into residential land.

Create a low entry level for those wanting to develop housing allotments. Smaller players need to be encouraged back into the market by abolishing compulsory so-called ‘Master Plans.’ If large developers wish to initiate Master Planned Communities, that’s fine, but they should not be compulsory.

Allow the development of basic serviced allotments ie water, sewer, electricity, stormwater, bitumen road, street lighting and street signage. Additional services and amenities – ornamental lakes, entrance walls, childcare centres, bike trails and the like can be optional extras if the developer wishes to provide them and the buyers are willing to pay for them.

No up-front developer or infrastructure charges. All services should be paid for through the rates system – paid for ‘as’ they are used, not ‘before’ they are used.

National or Federal Governments should consider using commerce or corporations powers to override state or city planning laws to allow land holders the right to make their land available for housing.

Similarly, National or Federal Governments which have state or city grants systems should reduce their federal grants commensurate with profiteering from land supply constraints driving up state and/or city tax revenue.

Countries which have strong competition laws should investigate state and/or city planning and/or land management agencies.

Cities should emulate policies where access to home ownership is made easy – Houston and Atlanta in the US, and adopt policies that reflect simplicity not complexity, neutrality not favouritism, transparency not opaqueness, and stability not instability as seen in cities listed on the UBS Bubble Index.

A United Nation’s sustainable development goal is “to ensure adequate housing for all by 2030”.

Without decisive action, this goal will never be achieved.

This article was first published by Bob Day in May 2018.